History

Egypt and Palestine

When the battalion arrived in Alexandria they were sent to the acclimatisation camp at Sidi Bish, just outside of the city, and it was here that they were to spend their first Christmas overseas. At Sidi Bish they were to learn the fate of one of their comrades who had been left for dead in Gallipoli. Rifleman Sid Porter had been seriously wounded during the first few days at Suvla Bay and had been left for dead after being hit by shrapnel. As the Turks searched the battlefield one of their officers saw that he was not dead so he was shot through the back of the neck to finish him off, he continued to live so a Turkish soldier bayoneted him, still he lived so he was bayoneted again but still refused to die. As the enemy started to try and bury the dead, Rifleman Porter still showed signs of life so they beat him about the head and shoulders with a shovel but still could not kill him, in the end, in sheer exasperation they gave up and took him prisoner. When he eventually reached the prison camp he was treated for seventeen different wounds, he fully recovered and became the camp barber. After repatriation at the end of the war he set up a business with his brother in Newport as a barber, this shop continued in business for over fifty years until failing health caused him to give up. The injuries he had suffered at the hand of the enemies earned Sid the nickname of 'The man the Turks couldn't kill.'

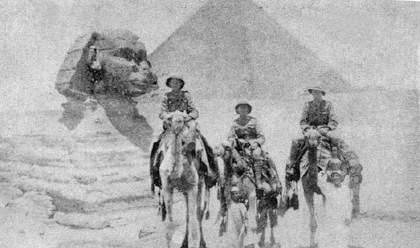

From Sidi Bish the Rifles moved to Mena Camp, a tented camp in the shadows of the Great Pyramids at Giza. Having received reinforcements to bring them somewhat up to full fighting strength the battalion then started training in earnest for the coming advance into Palestine. While they were at Mena a number of the men transferred to the newly formed Machine Gun Corps. From April until December 1916 the battalion occupied positions near the Bitter Lakes on the Suez Canal line. Meanwhile, back in England the second battalion had continued to train and build up its numbers after sending two drafts of reinforcements to the first battalion. The second battalion manned several of the Island forts including those at Puckpool and Culver until they were sent to Parkhurst barracks, from here they went to Nunwell Park and completed their training with the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry. From Nunwell, during the early part of August 1916 a draft of some two hundred and fifty men was sent to Romsey to join the 4th Hampshires. During September a large contingent of the 4th Hants, including the 250 men of the Rifles embarked for India under the command of Captain J. T. Fardeli of the 1st Battalion. Capt. Fardell had only been back in the United Kingdom a few months after returning from service with his own battalion on Gallipoli. The 2/4th Hampshires were stationed at Quetta in India for only a short time before they received orders to move, this time they were headed for Mesopotamia, following the footsteps of General Townsend and the 6th Indian Division. They sailed up the Shatt el Arab and landed at Basra and then travelled on by road and river to Baghdad, passing through Amarah, Kut, and Ctesiphon, the scenes of the 6th Division's battles and their historic siege. Most of 1917 was spent in Mesopotamia, the battalion then moved on into Persia and on into Russian Turkestan early in 1918. In Persia they had linked up with one of the famous Russian cavalry regiments, the Bickerakoffs Cossacks.

This detachment of the Rifles saw no major actions but were constantly engaged in minor skirmishes with the enemy until they eventually returned home early in 1919 after passing through Constantinople, Salonika, Italy and finally France.

In January 1917 the 1st Battalion moved back from the Bitter Lakes to Moacsar on the canal near lsmalia where they were to concentrate in preparation for the coming march across the Sinai Desert. The build up to this march began in January 1916 when, for a period of six months, the British Army under the command of General Sir Archibald Murray had extended the defences of the Suez Canal eastwards into the Sinai Desert. On August 3rd 1916 the battle for Romani took place, the enemy were some 15,000 strong and were commanded by a German, General Kress von Kressenstein. The Turks counter attacked but eventually withdrew after Murray's force had inflicted somewhat over five thousand casualties on them. By the end of 1916 the British advance had reached El Arish and January 1917 saw the Sinai completely cleared of all the enemy forces. The situation remained thus until preparations were completed for the advance on the town of Gaza.

The march of the Isle of Wight Rifles across the Sinai was recorded briefly by the late Lt. Col. Brannon (Lt. at the time) in a diary which he kept, contrary to regulations, whilst he was on active service. On Thursday the 1st of February 1917 the battalion left Moacsar in full marching order and they marched until they reached El Ferban where they bivouacked for the night, on the following day the march reached the town of Kantara. At Kantara all wheeled transport was surrendered and for three days the only transport was mules. These three days saw the march progress through Gilban, Pelusium Siding and on to Romani which they reached on the 5th of February. At Romani the battalion was to spend a week resting having already covered sixty or seventy miles of desert in a mere five days. Prior to leaving Romani the battalion drew its new first line transport, this was to be their first experience of camels as a form of military transport. The march continued through Rabah, Kibra, and Salamana to Mazar where the battalion arrived on the 16th of February. At Mazar the camels were handed in to be returned to the Camel Corps and tents were drawn for the future accommodation of the battalion. After a seven day rest the battalion was again to continue its march across the desert eventually reaching its destination at El Arish on the 26th of February, having covered a total of one hundred and forty five miles of desert in twelve days marching, this does not sound much but one must consider that they were in full marching order, travelling over some of the most barren country in the world in a terrible heat.

At last the Rifles were back in the front line and ready to face the might of the Turkish Army again. March the 26th saw the start of the first battle for Gaza but the Rifles did not get involved in this action as they were held in reserve. By the early hours of the 26th March all the British troops were in position, in the Wadi Ghazze and their supplies had been brought as far forward as was practical. Unfortunately at about 4 a.m. a fog rolled up from the sea and within an hour it was so thick that visibility had been cut down to about fifteen yards. The inevitable result was confusion and delay, and instead of the various units being in their appointed positions and ready to attack at 10 a.m. it was not until well after noon that all units finally engaged the enemy although sporadic encounters had been going on all morning with odd groups of men running into the enemy in the fog. Despite the delays and difficulties, the attack proceeded briskly once it had started. The main infantry attack was delivered by the 53rd Division and it made good progress towards Ali Muntar. On the southern and eastern sides of the town the mounted troops moved forward with fine energy, helped considerably by the preoccupation of the Turks with the frontal attack by the infantry. But as the Australian and New Zealand troops closed in on the town from the north east the resistance stiffened and a fierce fight developed among the cactus hedges which impeded the advance.

The infantry attack had been conducted with steadfastness and gallantry, the 53rd Division had advanced across badly exposed ground, meeting stiff resistance all along the line but by four o'clock they had reached the Turkish positions along the top of the Ali Muntar Ridge. A spirited rush by eighty men of the Welch Fusiliers carried them into the Turkish trenches, and although the enemy put up a good fight the position was taken. Earlier in the day the 160th Brigade had taken a very strong position known as the Labyrinth and, helped considerably by the accurate artillery fire the division had captured the entire Ali Muntar defences by 6.30 p.m., and everywhere the Turks were retreating into Gaza itself. By nightfall the town of Gaza was completely surrounded and it appeared that victory had been achieved. Unfortunately the excellent progress had not been accurately reported to headquarters and the news of the capture of Ali Muntar did not get through until very late the next morning. Headquarters appear never to have received an adequate picture of the progress of the battle and had laboured under several delusions as to the exact location of the various units. Early in the afternoon reports of enemy attacks from the east had convinced H.Q. that the position was serious and they ordered the 54th Division to move out into its allocated position along the El Burjabye ridge and to make contact with the 53rd Division on its left. The point of contact of the two divisions was supposed to be one mile north of Mansura. The 53rd was never informed of this move so the link up never occured. At 5.30 p.m. the Turkish relief column launched a strong attack. By good fortune the 7th Light Car Patrol was nearby and covered the withdrawal of the mounted troops. On the 27th of March the 53rd mistakenly withdrew from the Ali I'lluntar position, later that same day, after linking up finally with the 54th they reoccupied Ali Muntar, they had not the time to consolidate before the Turks energetically counter attacked. After suffering heavy losses the whole of the Ali Muntar ridge was evacuated and once more left in the hands of the Turks. Before daybreak on the 28th the 53rd and 54th Divisions had recrossed the Wadi Ghazze and thus ended the first battle of Gaza which cost the British Army nearly four thousand casualties. This battle could have been the decisive one but once again the attack had not been pressed home hard enough or for long enough. At the moment the withdrawal had been ordered the Turkish defenders of the town had been looking for someone to surrender to and could hardly believe their eyes when they saw the British retiring all along the front. This breathing space given to the enemy gave the Turks the time they so badly needed to reinforce their positions and to fully strengthen their defences along the line from Gaza to Beersheba. By the time the British were ready to launch a further attack they were to find an extremely heavily fortified line waiting for them.

During the spell in Egypt the command of the battalion had passed to Colonel Holland of the Devon Regiment who was taken ill shortly after the first Gaza battle and was shipped back to hospital. Major Marsh was promoted to Lt. Colonel and was appointed to command the battalion for the second time. This appointment met with the whole hearted approval of all ranks as Colonel Marsh was, at that time, by far the most popular officer in the battalion. Early April 1917 saw the battalion preparing for the coming offensive against the Gaza line. On the night of April 16/17th the second battle for Gaza began, in the attack each infantry battalion was supported by one or two tanks, this was the first time the men of the Rifles had seen those mechanical horses in action. One of the battalion's supporting tanks was named 'War Baby,' this vehicle managed to get very close to the enemy defences before receiving a direct hit and bursting into flames. One of the Rifles dashed into the flames and dragged out what was left of the crew, some living and some dead. For his heroism in the inferno of that wrecked tank Rifleman Bill Mowbray was later awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. The losses suffered by the battalion in this action were very high and many such similar acts of great bravery were performed (although very few of them were officially recognised). Rifleman Bill Ward recalls that he had seen one of his friends go down and when he approached to see if he could render any assistance was told "Get away from me, you'll only make us a bigger target for the Turks to hit."

It later turned out that his friend, Riflman Ernie Parsons had not been hit himself but was tending the wounds of the officer for whom he had been acting as batman. Here we take up the story in Rifleman Parsons own words: "At 7.30 in the morning we went over the top. the ground was almost as smooth as a football pitch and we didn't stand a hope in hell. We got three parts of the way over to our objective when my officer, a Lt. Butler, went down, he had been hit in the side. As I knelt beside him dressing his wound a piece of shrapnel hit my helmet taking the peak completely off of it. Bullets were flying all around us. As I got Lt. Butler to his feet and started to help him back to our lines he was hit again, this time in the foot. I continued to drag him back and eventually reached the safety of our own lines. I later travelled with him as his batman to Kantara and then on to Cairo where he was to go into the hospital and I was to rejoin the battalion. He fully recovered and returned to his home in Australia."

Rifleman Parsons was awarded the Military Medal for his gallantry in rescuing Lt. Butler at the risk of his own life and Lt. Butler wrote to Mrs. Parsons after the award had been made: "I want to congratulate you and your husband on the distinction that has fallen on you all by your son winning the Military Medal for his conduct on the 19th of April and for his particularly good service ever since he joined the Regiment. I know how proud you will be of him and he fully deserves it. You will see now that the high opinion I have always had of him is shared by his commanding officer. Your son was with me when he was told by the adjutant of his being awarded the Military Medal and his first thought was of the pleasure it would give his mother. He is fit and cheerful as ever, always ready for anything especially to help someone else." Rifleman Parsons own comments on the battle were summed up by him as "I thought that Gallipoli was bad but this was three times worse... I'm very lucky to be alive and never thought that I would get out in one piece." (He was later to be wounded in the third battle of Gaza).

The 19th of April was intended to be a major assault on the Turkish lines but after slight initial successes in the night attacks on the enemy outposts the daylight attacks became a disastrous failure. The Isle of Wight Rifles left two hundred men in reserve and went into battle eight hundred strong, at the roll call on that same evening only two officers and ninety men were there to answer. The casualty figures for the other battalions taking part in this battle were all very high owing to the heavy fortifications that the enemy had erected and the ferocity with which the Turks defended their lines. The following is an extract from the 'Egyptian Mail' published in Cairo on the 5th of May 1917.

From March the 27th to April 17th there was a period of very intense preparation and there was an electric feeling in the air. The troops were in very high spirits, largely due to the fact that they had left the desert and were now in the orange groves in the area surrounding Gaza. Before dawn on the 17th of April part of our infantry began to advance. As dawn broke the roar of artillery could be heard and high explosive shells were to be seen bursting over the enemy positions. The operation however was not without its difficulties, one part of the movement had to be carried out along an irregular ridge and another across the Wadi el Nakhabir, a maze of watercourse with almost vertical banks. The movement had however a certain element of surprise with our mounted troops operating far out on the right and our artillery shelling all the Turkish positions. The surprise did not last long and the enemy was left in no doubt as to our intentions. The English and Scottish Territorial divisions were able to move forward with surprising rapidity, establishing themselves without suffering too severely, in strong positions along the crests of the Sheikh Abbas and Mansura ridges. The opposition met with was easily turned aside, in one instance a whole brigade reached its objective without suffering a single casualty.

On the 19th we pushed forward on the left to within three thousand yards of the town of Gaza and drove the Turks from their observation posts and their strongly entrenched positions on Sampsons Ridge. One could see wave after wave of men advancing from ridge to ridge accompanied by tanks. There was a brief pause as the attack neared its objective, then with bayonets flashing in the sun our men swarmed around the flanks of Sampsons ridge. One of the tanks went steadily on and it attacked the next redoubt and speedily put the entire enemy garrison hors de combat. The troops on this flank now established themselves along the north of the ridge from Sheikh Ajlin in the East, westwards towards the coast. This line was extended to the east until it came into contact with the units which had advanced in the centre. In the centre the Scottish divisions had the difficult task of capturing a series of strongly held ridges up to Ali Muntar. They advanced with splendid gallantry and steadfastness in the face of deadly machine gun fire until they reached Outpost Hill. On their right the English Territorials also had a difficult task, they had to advance across open country offering no semblance of cover, they encountered tremendous resistance but they pushed on with fine determination and captured positions to which the enemy attached so much importance that they launched five separate, very heavy counter attacks in a vain attempt to recapture them."

Rifleman J. R. Toogood was one of those wounded in the second battle and he wrote home to his sister from the hospital at Alexandria; "No doubt you are worrying greatly about me but I have been unable to write. I am wounded in two places with shrapnel in my left arm and a machine gun bullet through my right lung but I am improving. I had such a terrible experience that I did not expect to be alive now. It was Thursday the 19th of April that this happened. At dawn on the Tuesday previous we took a place and held it until Thursday when we were ordered to go over the top to another position. It was like being at South View (Newport) and the Turks at Elm Grove across Nine Acres Field. But instead of nine acres it was just over two thousand five hundred yards, all wide open country with no cover. First one side of me then the other, my comrades were shot down and big shells were dropping all round us, then my officer got knocked off his feet and those of us who were left went on with the advance until we were less than a hundred yards from the Turkish trenches. We stopped here and made up our line but could do nothing to help us advance further. I was expecting to be hit every minute, then a shot went through my helmet and took a piece out of my tunic but it did not touch me. Then another hit my back and then a shell pitched down beside me and I thought it was all up. A lump of shell hit me in the left arm and the blood began to flow. I took off my tunic and pack and stood the pack in front of my head, then I took off my water bottle and started to run back, dragging my tunic in my right hand. Then they turned a machine gun on me, they riddled my waterbottle and then a bullet went into my back, through my right lung and came out about a quarter of an inch below the hollow of my throat. I could not go any further, blood came like a fountain from my chest and back and my lung began to fill with blood. I jumped into a shell hole about a hundred and twenty yards from the Turks, and there were six other wounded there. A stretcher bearer from the Norfolk Regiment patched us up with field dessings. One of our officers was in the same shell hole with us and he gave each man a mouthfull of brandy. We were laying there in the boiling sun, almost dying for the want of water. I was wounded at about 10 a.m. and had to lay where I was until at 1.30 p.m. I saw several of our chaps jump over our shell hole and I asked them what was the matter, they said that they were retiring, and I knew it meant certain death to stay where I was and possible death to try and get back, in the end I decided that I would be better off trying to get back to our own lines so I jumped up, and leaving the others, started to run as fast as my left lung would supply me with wind. One chap carried my tunic and eventually I managed to reach the Advanced Dressing Station. How I got back without being hit again do not know. I stayed at the dressing station until it. got dark and thecarts were able to come up and at last I was taken to a temporary field hospital where l had my wounds redressed. I would nearly as soon die as go through that again. I suffered much pain. The next night I was brought across the Sinai Desert to Kantara and am now in hospital in Alexandria, I had to lay on my back until Monday then I was propped."

During the second battle of Gaza, a large number of men from The Rifles were wounded and later taken prisoner by the Turks. Rifleman Rowe was one of these, he had been hit in the knee and was left on the battlefield when the battalion retired, he remained laying injured on the battlefield for three days and three nights until he was found by an Armenian doctor and a Turkish Red Crescent soldier. After he had been roughly patched up by the doctor he was dumped, along with several of his comrades, into one of the Turkish trenches to await transport to take them back to hospital. During the first few days of their captivity, the wounded were roughly treated, and the enemy soldiers stole anything that took their fancy, Rifleman Rowe lost his boots, socks and underwear, his first stage of travelling ended in the Turkish Number 18 Military Hospital at Nazareth where he remained for several weeks before being moved on to Constantinople, and it was while the wounded prisoners from the 54th Division were here at Scutari prison hospital that they were visited by General Townsend, the erstwhile commander of the 6th Indian Division who had been captured after the heroic siege of Kut. During November, 1917, a large number of wounded men were transferred from Scutari to the Austrian Prisoner of War Camp at Mauthausen, just outside of Vienna. Rifleman Rowe recalled that he arrived at Mauthausen on the 4th of December and he remained here for about two months, the worst part of the winter. Conditions in the Austrian P.O.W. Camps seem to have been tolerable, the men were reasonably well treated although their food was very poor, this being due to the fact that their guards had only meagre supplies for themselves without having to feed their 16,000 prisoners as well. The daily rations consisted of a bowl of soup in the morning with a small piece of hard black bread, a second bowl of soup during the evening completed their diet, this diet was never varied. At Mauthausen Rifleman Rowe was to find three other men from the Rifles, these were Riflemen Legg, White and Thomas. In February, 1918, a small number of the wounded were repatriated to England, these included Rifleman Rowe, they travelled via Switzerland and France, leaving France on board ship from Rouen, they were to disembark at Southampton, they arrived at the King George Hospital at Waterloo on Monday, the 18th of February, 1918, for them the war was finally over.

At the end of April, 1917, General Allenby took command of the army in Egypt and started to regroup his battalions for a further push against the Turkish line. During the months of spring and early summer, the Isle of Wight Rifles took part in several minor probing raids against the enemy. One raid in particular, was planned down to the last detail and thoroughly rehearsed for several weeks, it was to be against the trench system that our troops knew as the 'Beach Post,' it was right down on the coast and was a fairly large system. On July the 14th, the attack took place, it went like a well oiled machine, all its objectives being obtained. The battalion took nineteen prisoners and inflicted a further sixty or so casualties on the enemy. Lt. C. W. Brannon was awarded the Military Cross for his gallantry when leading his men into this attack.

On October the 31st General Allenby launched his attack on the Gaza to Beersheba line, three divisions including the Isle of Wight Rifles took part in a diversionary attack on Gaza itself, while the main force wheeled northwards to attack Beersheba. The battalion did not suffer too heavily in this engagement although several men were killed and a number wounded. Rifleman Ernie Parsons, M.M., recalls how he had found a fairly large quantity of cigarettes in a dugout that had only just been vacated by the Essex Regiment and whilst he was discussing his find with Colonel Marsh and some other men who had come up to see what was going on, a shell exploded overhead and of the dozen or so men there at that time, Rifleman Parsons was the only one to be hit by the shrapnel. He lay in the dugout all day until it got dark, then he was evacuated to the hospital at Kantara. One of the battalion's losses at this time was a young officer who had been seen going over the top after telling his men that he was going to avenge his two brothers who had perished on Gallipoli, this young man was Lt. Stephen Ratsey and he was never seen again. Another well known member of the battalion who was injured was Gordon Harker, the actor, who had served with the Rifles at Suvla Bay and had taken part in the march across the Sinai. He was hit in the shoulder and the thigh and would have died had he not been found by Company Sergeant Major Early and Rifleman C. Gifford. Although these two men were both badly wounded them- selves, they attempted to drag Lt. Harker back to the first aid post. Owing to the severity of their own wounds, they were unable to complete the journey, they left Lt. Harker and continued on their own until they found some stretcher bearers whom they persuaded to come with them. They led the bearers back to Lt. Harker and only then would they allow the orderlies to dress their own wounds.

B.O.M.S. Herbert remembers how, one night on Sampsons Ridge, he was leading a patrol of five men along the ridge top, they had been given express orders that they were not to engage any enemy patrols that they might come across unless it was absolutely unavoidable. These orders had been issued as the enemy usually sent out patrols of about fifty men. As our patrol moved along the ridge in briliiant moonlight, a movement was spotted about two hundred yards in front of their position, the patrol dropped as one man to the firing position, after some minutes the movement was still continuing and so a challenge was shouted out, this was done several times with no answer and the movement still carried on. Eventually the patrol opened fire on the area concerned, but still received no answering fire. By this time the whole of the British lines had stood too, thinking that it might be the start of a major Turkish counter attack. It later turned out that the movement had been an empty sandbag tied to a post, and this was blowing about in the wind.

The post was, in fact, a marker for the Turkish artillery. With the fall of the enemy line, the battalion moved on into Palestine and eventually helped to establish a line north of Jaffa and Jerusalem.On the 13th and 14th of November, the battle of Junction Station took place and Allenby's force drove the enemy back towards Jerusalem. General Von Falkenhayn had assumed command of the enemy forces in Palestine but he was unable to have any effect on the outcome of the following battles and Allenby's army managed to occupy Jerusalem on the 9th of December, the Rifles were not present, they were dug in on the Judean hills and fought a rather long and drawn out battle here. On the 26th of December, the enemy launched a major counter attack on Jerusalem but were beaten off with heavy losses. In the period of January, 1916, to December, 1917, the total British losses amounted to just over eighteen thousand men and the enemy lost twenty-three thousand, including eleven thousand five hundred taken prisoner. The Turks also lost over one hundred guns that had been captured intact by the British.The Rifles remained in Palestine right through 1918 until, in September, General Allenby launched his final offensive as a result of which the Turkish army was largely encircled and captured or destroyed. On the 11th of November, the battalion was still continuing to advance northward, they were in fact about thirty miles north of Beyrout when hostilities finally ceased. They were shipped out from Beyrout back to Alexandria and on to Cairo. In Cairo demobilisation started, this was to be halted in 1919 when severe rioting broke out in Egypt. In a show of force, the entire 54th Division was marched right through Cairo and General Allenby took the salute at a march past. During this time the Rifles were stationed in the Kas el Nil. Barracks in the centre of Cairo.

Once the riots had been quelled, demobilisation continued, a cadre of volunteers was also formed at this time, this detachment under the command of Colonel Marsh were sent to Khartoum as a unit of the Army of Occupation of the Sudan. When these men returned home in 1920, Col. Marsh remained in the Sudan where he took up the duties of a District Commissioner, a position in which he served with distinction for many years before he retired and returned to the United Kingdom to settle down. Major Carwardine brought the cadre back to England and they eventually arrived on the Island on the 24th of March, 1920, and they received an official welcome.

Due to the similarity of the uniform of the Rifles to that of the Ghurka's, the battalion obtained a new nickname for itself during the First World War, they were known as 'The Isle of Wight Ghurka's.' This name was to stick, even after their conversion to artillery in 1937.